So, I try hard not to get too promotional gloppy and horn-tooting here on the blog. But there is one little thing I've made a tradition of, so indulge me for the day. That's the first review. Y'know, us'n authors are supposed to be all cool and uncaring but I can't lie on this score: the first review is a groovy thing. You work 3 years on something, it's nice to wake up one morning and read someone saying, "Hey, this novel doesn't suck." The first review of The Ice Beneath You came from Publishers Weekly (which, back in the day, was the location of all first reviews; not so much anymore). If I recall correctly, Voodoo Lounge got a three-way tie for first review, because I heard about Details, Booklist, and Bookslut.com all on the same day.

And for In Hoboken? Turns out of all things the first review is fromThe Star-Ledger (for those of you who don't live in the greater New York-New Jersey area, that's the paper that used to slam down on Tony Soprano's driveway every morning). Can't argue with the cosmic appropriateness of the venue.

***

The Star-Ledger

"Ambling to their own beat"

Sunday, March 23, 2008

REVIEWED BY BETSY WILLEFORD

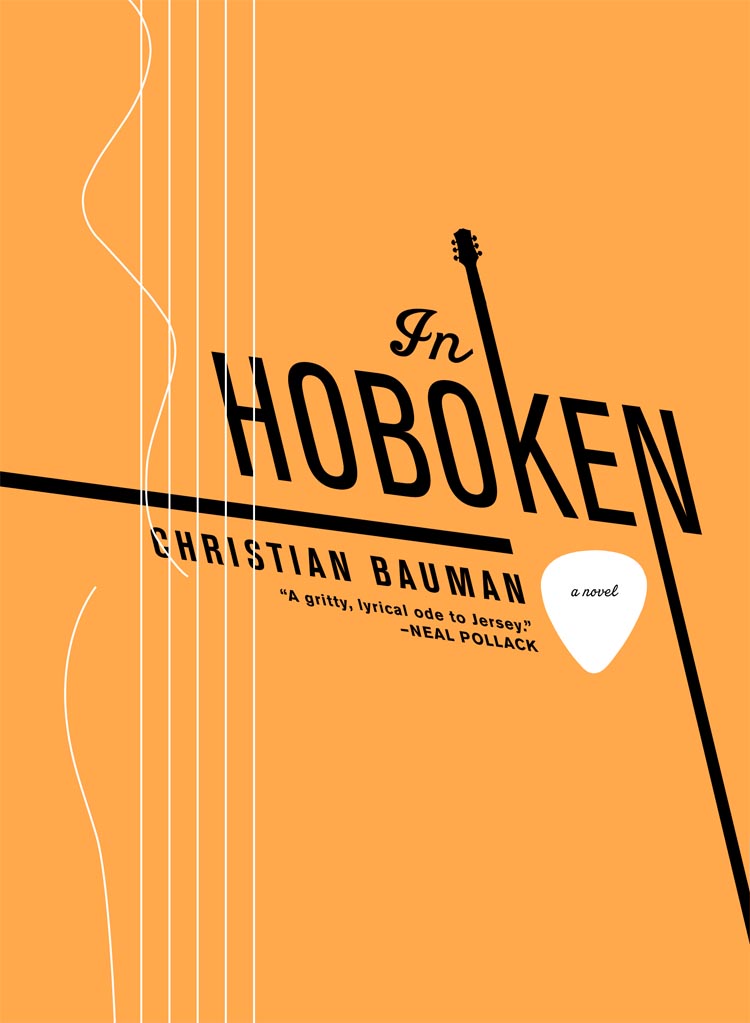

In Hoboken

a novel, by Christian Bauman

In 1995 gentrification is merely nibbling at the edges of the "mile-square city." Bauman's characters live in sixth-floor walkups; use pay phones, not cells; eat in unretrofied diners. Some commute to day jobs across the Hudson. But music is the passion that draws them together -- wood music, folk songs they write and play on acoustic guitars, earning "tens of dollars." There's also an artist, and a pair of buddies right out of Simon and Garfunkel's "Old Friends" who spend the day at the local behavioral institute, formerly the mental health center.

Remarkably, for an ensemble story, Bauman has created nearly a dozen fully rounded characters, each of whom could be the core of a novel.

Thatcher Smith, 24 and newly released from the Army, and his high school friend James, recently released from Rutgers, both amble in slow diagonals when they walk, a block up, a block over, taking it all in, the crowd flowing around them.

That's how Bauman tells his story, too. Marsh is a middle-age dad with a lifelong polio limp, eking out a living promoting marginal groups to marginal album labels. Quatrone is the painter who lives with his 80-year-old mom in an apartment downstairs from James. Bruno, who works in Manhattan, had a minute of almost-fame on a Bananarama tour in the '80s. Lou is a singer whose departing lover schleps her to a shrink for "closure."

A lot of comic stuff about language here, but so deftly interwoven you have to read the novel at James' walking pace to notice. Orris, one of the day patients -- clients, they're called -- at the behavioral institute where Thatcher works as a file clerk, remembers that when one of his friends died, the hospital staff didn't want him going to the funeral. "They think the funeral might be disturbing."

A lot about Hoboken, too. Elysian Field, where Alexander Cartwright's home team lost the first recorded baseball game, 27-1, to the New York Knickerbockers. Guglielmo Marconi -- who, it could be argued, made Frank Sinatra possible -- lived in Hoboken. Willem de Kooning supported himself as a sign painter for a year before crossing the Hudson.

Quatrone explains to Thatcher how de Kooning's early work has changed over time because of the materials he used. "Materials decay." Like a song, Thatcher thinks: You play it, and it's yours. And then immediately it's not.

Bauman's throwaway lines resonate. He's wise enough to let the echo do the work. Having helped his son move furniture into the sixth-floor apartment, James' father says, "I worked my whole life to keep you out of this." This being the Hoboken that energizes Bauman's people and his story. No easy revelations or resolutions. The material is frayed at the start, loosely woven at the conclusion, a year in the life.

Tempting to call the book a tour de force, but that suggests a neon light flashing a*c*h*i*e*v*e*m*e*n*t. What's amazing about "In Hoboken" is you're unaware of the writer's hand.

***

Having been on the receiving end of reviews that -- even when positive -- were clearly written by someone who didn't "get" the book, I can't tell you how nice it is to have the first review of In Hoboken be by someone who so clearly got it. A nice feeling. And now I can go back to pretending I don't care what the critics say...

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

LIVING ON THE EDGE OF THE WORLD: includes alt excerpt from In Hoboken + pieces by Tom Perrotta, Jonathan Ames, Joshu Braff, James Kaplan

WAR IS: My essay "Letter To A Young Enlistee" along with Dylan, Hedges, Twain, and amigo Turnipseed

BOOKMARK NOW: My "Not Fade Away" with Nell Freudenberger, Tracy Chevalier, Meghan Daum, Tom Bissell

NOT LIKE I'M JEALOUS OR ANYTHING: daughter Kristina and I contributed a short story to this cool YA anthology

WHAT EVERY PERSON SHOULD KNOW ABOUT WAR: I was happy to be part of the group of vets and students who helped Chris with this book

MAN, YOU SHOULD HAVE SEEN THEM KICKING EDGAR ALLAN POE.

ABOUT

CB IN OTHER BOOKS

LIVING ON THE EDGE OF THE WORLD: includes alt excerpt from In Hoboken + pieces by Tom Perrotta, Jonathan Ames, Joshu Braff, James Kaplan

WAR IS: My essay "Letter To A Young Enlistee" along with Dylan, Hedges, Twain, and amigo Turnipseed

BOOKMARK NOW: My "Not Fade Away" with Nell Freudenberger, Tracy Chevalier, Meghan Daum, Tom Bissell

NOT LIKE I'M JEALOUS OR ANYTHING: daughter Kristina and I contributed a short story to this cool YA anthology

WHAT EVERY PERSON SHOULD KNOW ABOUT WAR: I was happy to be part of the group of vets and students who helped Chris with this book